The South Sudanese public is eager to hear news about the peace deal and reforms, but journalists say it can be difficult to get information from government agencies.

Koang Pal Chang, chairman of the National Editors’ Forum, said access to information can be a problem for journalists who want to dig deeper into matters of public interest.

Moyiga Nduru, the access to information commissioner, denies that the government is withholding information. He said those who have problems accessing public sector or government records can come to the commission and file a complaint.

“We are dealing with cases. If they [the government] don’t want, then you come and complain, fill out a form and then we write to government officials,” Nduru said.

The media say the public is looking for more in-depth information on politics and security.

Like many in South Sudan, Panchol Yohana, 55, turns to the radio for credible news and information. “I listen to political programs. And I love having a radio since I was a young boy in school,” Yohana told VOA. “When information circulates in the neighborhood and does not come from the radio, I do not consider it because the radio did not cover it.”

Yohana said news on the implementation of the 2018 peace agreement on resolving the conflict in South Sudan is among the topics he follows regularly.

Other times, he listens to the radio to relieve stress.

“When I don’t listen to the radio, I don’t feel mentally happy. But when the radio is next to me, I focus on the program and it clears my mind. I constantly listen to it until I forget the stress that was on my mind,” Yohana said.

The peace accord and a unity government were formed in an attempt to end violence and a 5 ½ year civil war in South Sudan. The war is estimated to have killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions from the region, according to the Council on Foreign Relations’ Global Conflict Tracker.

Jacob Alier, another radio listener in Juba, said he sometimes noticed a lack of information on vital national issues when listening to different radio stations.

“We are missing a lot of things. A lot of Jonglei citizens are saying here, people don’t know about it,” Alier said, referring to the provisions of the peace accord.

“If people are allowed to play their part, they can give us a lot of information,” he added.

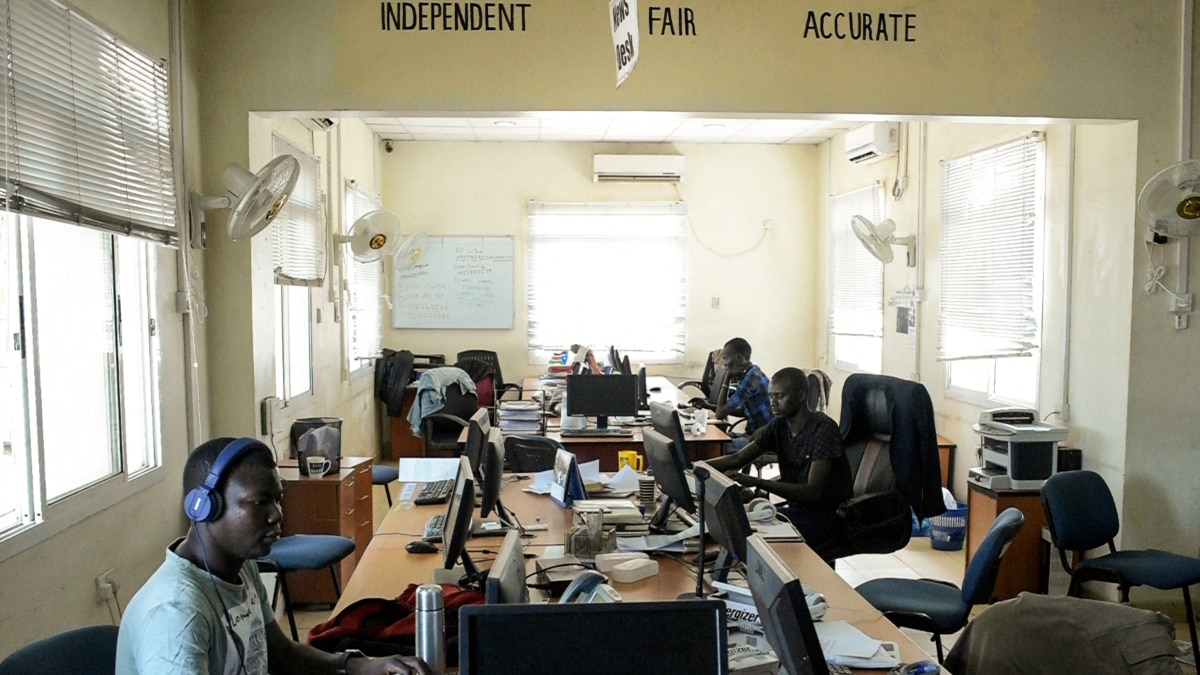

Some media outlets said they go to great lengths to provide credible information to their audiences.

Pal Chang, who is also Eye Radio’s program manager, said his station tends to focus on things he thinks Juba listeners are interested in, but it can be difficult to get the information.

“We don’t get enough information about reforms, for example,” Pal Chang said. “What is happening in terms of reforms? Because the peace agreement talks about reforms. [the] financial sector, [the] economic sector, in governance. These things nobody talks about, and when you ask, nobody wants to give you information.

Japheth Ogila, editor of City Review, said he has noticed an increase in interest when the Juba-based newspaper covers security issues.

“We realized that most readers in South Sudan buy newspapers when our headline talks about security related things or humanitarian issues like hunger or floods,” Ogila said.

South Sudan ranks 139th out of 180 countries, where 1 is the freest, on the World Press Freedom Index.

Media watchdog Reporters Without Borders said the country’s media could not cover issues related to the conflict and that harassment, arbitrary detention and intimidation were also problems for journalists.

Last month, police briefly detained eight journalists who were in parliament for a press conference over allegations of intimidation against opposition media outlets and politicians, according to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists. . Two of these detained journalists contribute to VOA.

Security services at the time said the briefing was illegal.

This story originated in VOA’s English to Africa service.